This week I’m changing things up a bit to dive into a subject that is close to my heart, but also a part of ice hockey that is both vital and suffering – officiating. As editor of TJHP I feel it’s appropriate to point out that in addition to being a club operator and Junior team owner, I was also an on-ice official for many years.

I dropped my first puck in 1979 at an outdoor arena in Fergus Falls, Minn. I dropped my last puck in March 2008 at the Richmond (Va.) Coliseum during at a Southern Professional Hockey League game. In between I was fortunate enough to travel all over the country while working more than 1000 games, including a few hundred at the minor professional level and four USA Hockey national championship games.

That is not a resume for the sake of sharing a resume, but more to point out that I’ve been in the locker room at 6am for a Mite game and at 6pm for a professional game, and everything in between.

This editorial may go back and forth between the hockey side of the game and the officiating side of the game. A select few of us have been heavily involved on all sides of the game. My contention has always been there shouldn’t be sides. A hockey game involves everyone on the ice and on the benches, which includes the officials.

Many fans, players and coaches view officiating as a necessary evil. However, in the roughly 140 years that organized ice hockey has been played, there has yet to be a legitimate contest that took place without referees.

Because this site is dedicated to college-bound hockey, this editorial will mostly address how the shortage of officials affects the 16U, 18U and Junior levels of hockey. However, this is only the tip of the iceberg given the vast majority of players, coaches and games that are present far below these competitive levels.

Right from the get-go, officials are rarely treated as being inside the hockey “tent.” At the grass roots levels officials are frequently treated as being part of an outside organization. Not on a personal level, but officiating is nothing more than a task that a club scheduler needs to handle with the local referee assignor.

There is little thought at any board of directors meeting, or with for-profit hockey ownership groups, about the officiating part of the game even though they constantly meet about how to develop their players and their organizations. Players and coaches train and develop in order to display their talents during a game – which always involves officials – but not thought is given to the referee and his or her crew.

At the high level 16U, 18U and Junior league levels, officiating is again treated more like an outside vendor with which the league executives need to communicate and pay. In a Junior league there is a lot of interaction between the coaches and the Referee-In-Chief, but almost always when addressing supplemental discipline issues or when a league allows coaches to challenge – via video – the calls of the officials (or their perceived lack of calls). As technology has advanced, so has the ability to scrutinize, edit and present – often in slow motion – a coach’s subjective viewpoint on calls and on-ice issues.

This has all resulted in a fairly wide chasm between officials and the actual teams that play in the game, which is ironic because they all show up, warm up and suit up on game day. The puck doesn’t hit the ice unless a referee drops it.

When USA Hockey rolled out its Coaching Education Program (CEP) in 2000 I spent two years traveling to coaching seminars with the Potomac Valley Amateur Hockey Association’s first coach-in-chief, Patrick Keough, speaking at seminars about officiating. I didn’t realize Keough’s approach was both ahead of its time but also unique in that other affiliates weren’t required to feature in-depth information on officiating. Right from the beginning of the CEP program a big opportunity was missed to fill in the chasm.

The overall shortage of officiating is a real thing. For years referee supervisors and USA Hockey have been warning that as the game grows, and team counts grow, so do the number of games being held. More games mean more officials are needed.

Even as an active referee these warnings sounded a little like Crying Wolf to me because I never experienced it despite being involved heavily on both sides of the game. Despite USA Hockey’s efforts to decrease attrition and attract former players to officiating, the numbers have continued to get worse. The worst time to manage a problem is after the problem has grown to the point of affecting the product or the outcome.

In the past two years reality has hit. All over the country games are essentially turned back to the organizations because there are no officials who can work. Truth be told, most of these games are likely added on short notice. In the old days if two coaches decided on Wednesday night to play a game the upcoming Saturday, the officiating supervisors would scramble to find officials and generally they could manage. Now the officiating supervisors are simply scrambling to fill games that are submitted weeks or months in advance.

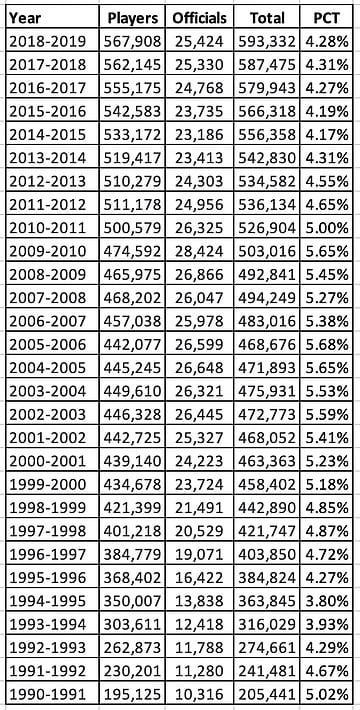

The chart to the right shows how player registration has increased over the past 29 years, while displaying how officiating numbers have not kept up. Adding in the increase in team counts via spring and summer hockey and the growth of club-level high school hockey, and the problem is magnified more than these numbers point out. In the last 9 years the number of registered players has increased by almost 100,000 while the number registered officials has dropped by 3000.

Let that sink in for a minute.

To compound matters, the number of registered officials isn’t even close to the actual number of officials who complete the lengthy certification process, become able to work a game — and then actually get an assignment and step on the ice. Many clubs force players into registering and attending referee seminars, which is great, but there is no intention to actually become an official.

Scheduling officials has now become a first come first served situation. The sooner an organization can get its games submitted the better chance it will have of getting all games assigned. This method has no quality control since the procrastinators likely have some very high-level games that need to be staffed, and when they get their games submitted all experienced officials are already committed. In a perfect world the officiating schedulers would have all their games submitted and could then assign officials with dual purpose of staffing with qualified referees and blend in developmental opportunities for young or up-and-coming referees.

At the higher levels of hockey, the NHL actually starts the ball rolling on how the officiating shortage manifests itself. During the season, there are certain Saturday nights when the NHL has 14 or 15 games. This means all their full-time officials are working the Big League that night (some officials work split schedules of NHL and American Hockey League games).

The openings in the AHL that night means ECHL, Southern Professional Hockey League and maybe Federal Hockey League officials get tagged to fill in. On the same night it’s likely that almost every NCAA Division I, II and III team is playing, and because a lot of experienced officials work both minor pro and college, it sucks up virtually every official who is capable of working those levels.

Then we move down to the Juniors, which as we’ve already discussed in past weeks is completely saturated with teams. Some Tier III games have only 30 skaters but it requires three or four experienced officials to work every contest. This taxes the officiating pool even more, but also starts to bring guys into the mix, who 10 years ago would have no chance at getting a Junior game assignment. Throw in the ACHA college games, which can also be high level and can pay very well, and many officials will simply work those games because they like that level.

Moving farther down to 16U and 18U levels, both of which are very skilled and very competitive, we have Saturdays and Sundays during which some teams play more than once. Again, we need three fairly experienced officials to work all these games. In some areas of the country high school hockey is big, and Friday and Saturday nights are filled with those contests.

You start to get the picture. By the time you’re looking at staffing a 7am Pee Wee game in a cold rink, there aren’t that many takers, if any. As independent contractors, officials have the option to say “no” to assignments or take weekends off to spend time with family. Some officials need to exercise that option more as doing five or six games per day will lead to a reduction in physical and mental acuity 100 percent of the time.

Throw in the fact that in many parts of the country players play travel hockey and for their local high school, plus the spring and summer teams that are becoming more and more popular and the officiating pool gets taxed more and more each year.

USA Hockey does a great job addressing officiating. It has been addressing the shortage of officiating, while also trying to develop high-level officials, for many years. The Officiating Development Program has been staffing leagues like the old American Frontier Hockey League (western United States), the United States Hockey League (USHL), the North American Hockey League (NAHL) and the Southern Professional Hockey League (SPHL) for more than 20 years.

The high-level opportunities and training have been around for a long time. What’s really held back development in the United States is the NHL’s passion for hiring Canadian-born referees and linesmen. As U.S-born players have increased to 26 percent of the NHL player pool, compared to 44 percent for Canadians, officials are just 19 percent U.S.-born and 80 percent Canadian-born.

The NHL notwithstanding, officials can develop well and climb fairly high up the ladder with the help of the USA Hockey program. Unlike players, when officials realize they are not going to be one of the elite who get hired by the NHL they can continue to work for years at very high levels of the game.

Very few of these officials, in whom USA Hockey has invested a lot of time and energy, matriculate back down to the grass roots levels to work with younger and inexperienced referees because – frankly – they are needed to cover the wealth of upper level games described above.

When two beginner officials end up in a 12U AAA game (for example) because of the shortage of officials, a common result is coaches yelling and screaming at the officials. Call it verbal abuse, call it bullying but the end result if a younger official who has very little support and very little experience to fall back on when dealing with irate coaches and parents. Leaving the ice surface and even leaving the building can literally be dangerous.

Who wants their 16-year-old son or daughter to be in a position to deal with crazy coaches or parents? The pay is not worth the anxiety, which is why USA Hockey cites a 33 percent attrition rate EVERY YEAR. Fifty percent of its first-year officials don’t come back for a second year. That’s a problem that will need to be addressed at all levels of hockey in order to solve. The quality and quantity issues that affect officiating will continue to persist because there is no solid plan to address throughout the sport.

I would recommend such simple measures like voluntarily capping game counts for all levels, increasing penalties and suspensions for coaches and parents who abuse officials verbally, elimination of coaches and parents who abuse officials physically and joint coaching and officiating seminars.

One of the biggest eye-openers for me when traveling with the PVAHA coaching seminars was the on-ice portion of the day. It seems cliché, but most of the coaches who were the biggest screamers and complainers couldn’t skate — literally — and it was clear very few of them ever played an organized game of hockey. When I saw them on the ice it made sense to me. Their lack of experience in the game manifested itself with bravado, and what easer way to hide your lack of experience by bullying?

Bringing beginner coaches into the same room with beginner referees, and likewise experienced coaches with experienced referees, would at least put names to faces. More data, more problems and more solutions could make this editorial even longer, but TJHP will continue to cover and dig into the relationship between officiating and the game of hockey in order to be part of the solution.

Jeff Nygaard is the editor of The Junior Hockey Podcast. He covers Junior and college-bound hockey as a traditional “beat,” in addition to breaking news stories during the course of the year.

He has a vast amount of experience on the business and organizational side of the sport as a former owner-operator of two Junior organizations two youth clubs and having served as executive director or commissioner of the Eastern Hockey League and the United States Premier Hockey League.

A Fergus Falls, Minn., native, Nygaard grew up playing for the Fergus Falls Youth Hockey Association, Fergus Falls High School, Fergus Falls Community College and North Dakota State University programs. He can be reached at info@juniorhockeyhub.com for questions, story ideas and anonymous tips.